A new study by the Serco Institute suggests that competition and contestability can play a major part in creating powerful incentives to innovate and implement reform

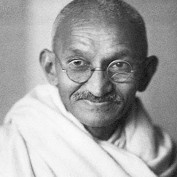

The American political economist, Aaron Wildavsky once wrote: "No genius is required to make programs operative if we don't care how long they take, how much money they require, how often the objectives are altered or the means for obtaining them are changed."

In the real world - where public service managers grapple with scarce resources, short time horizons and escalating demand - value for money matters. The challenge lies not so much in discovering what must be done, as it does in understanding how to create powerful incentives to innovation and the implementation of reform.

A new study by the Serco Institute suggests that competition and contestability can play a major part in creating these incentives. Competitive Edge looks at almost 200 government and academic studies of contestability in public services over 30 years, covering 12 countries and five different sectors.

The Institute's analysis of the published research found that financial benefits of 20% are not uncommon when public service monopolies are first exposed to competition and, in some cases, much more. While not all of these studies addressed the question of service standards, among those that did, there was little evidence that quality declined

.

The impact of competition

While many of these studies had focused on the comparative efficiency of the public and private sectors, the Institute tried to identify the impact of competition. With few exceptions, it was competition that made the difference, rather than privatisation. Where an in-house team won the right to manage the service following competition, they delivered financial improvements that were comparable to those delivered by private and not-forprofit providers.

In several cases, the Institute was able to go further than this and look at the impact made by the mere threat of competition - referred to in the report as the contestability effect. There is evidence that public service managers are motivated to overhaul the design and delivery of public services when they are faced with a credible threat of competition. For example, in New South Wales, the state government used the prospect of competitive tendering to renegotiate the management for three new generation prisons. When two of these were studied by the Public Accounts Committee in 2005, it was found that sick leave and overtime levels were significantly lower than at traditional prisons. But there is a limit to how often the mere threat of competition can be used. It's a bit like the boy who cried wolf - eventually you have to come good on the threat

.

Service redesign

Competitive Edge differs from earlier literature surveys in striving to understand the sources of these financial benefits. The evidence suggests that a significant proportion of these gains come from productivity enhancements, although it is difficult to say how much. However, the research does confirm that the process of competition opens the way for a fundamental rethink of the way in which the service is delivered. Incumbents face a major disadvantage in this regard, in that they already 'know' how the service ought to be delivered.

It seems that successful service managers develop a bespoke solution tailored to the problem in hand. In some of the studies they have significantly reduced the use of overtime, whilst in others they have relied on it more extensively. In some cases, they have turned to multi-skilling, while in other places they have turned to specialisation. Sometimes they used more part-time workers, other times they used fewer. Some providers introduced personal bonus schemes, while in other cases they abolished them. There is no single formula capable of being applied across the board. Successful service innovation seems to depend on the development of a unique design customised to meet the needs of the individual customer.

This process has been little documented and, understandably, among private providers there is some reluctance to share lessons that may provide them with a commercial advantage in future competitions. But the available evidence seems to suggest that service innovation is incremental in nature. Change appears to come from a multitude of micro-reforms rather than from major procedural and technological breakthroughs. This probably helps to explain the difficulty that researchers have had in identifying what contribution particular reforms have made.

This may also explain why the word 'flexibility' occured so often in the studies that addressed the sources of savings. Good service design needs the flexibility to adapt to local conditions, and to keep on adapting as those conditions change. It is difficult to understand how there can be continuous improvement unless service managers enjoy the autonomy and flexibility to experiment with alternative approaches

.

People management

Another part of the answer seems to lie in better people management - putting the right people in the right jobs, and using good people better. At its simplest, this is evident in the better management of sick leave and overtime. This emerged as a consistent theme throughout the research, from municipal government in North America to prisons in the UK and Australia. It was as evident among successful in-house teams as it was among external contractors.

Successful contractors seem to pay more attention to appointing staff that are more appropriately qualified for the job in hand. In both the US and Australia, this seems to explain the large savings in defence support, with the substitution of civilian personnel for highly trained (and thus more expensive) uniformed personnel

.

Innovation in prison management

Much the same has been evident in the UK prison management market: contractors have been able to reduce unit costs, in part, by recruiting younger workers who are at a different stage in their professional careers. Since service standards in the privately managed prisons have not been noticeably worse than in the public sector (and in some ways have been better), this suggests that this innovation has worked

.

Authority and technology

The evidence is clear that successful contract managers enjoy much greater autonomy than service managers working under a traditional public service regime. One North American study reported that contractors were much more likely than municipal agencies to make frontline supervisors responsible for hiring and firing and for the maintenance of their equipment. Cities with low costs required managers to accept responsibility for their staff, which reduced the tendency to pass the buck.

Technological innovation was a source of value for money improvements in some of the studies - a computerised inventory system in a military warehouse, or the use of CCTV cameras and electronic keys in new generation prisons. However, in the services addressed in this report, it was not mentioned as a major driver of change (although in other service areas, such as business process outsourcing, it would probably feature more prominently).

There is no doubt that in some jurisdictions at some times, cost reductions have been delivered in part through reduced terms and conditions for workers. This was particularly so in the UK in the 1980s and early 1990s under compulsory competitive tendering, although regulation and codes of practice now preclude such an approach. However, the research is clear that savings do not have to be made in this way - service redesign and better people management are capable of delivering real productivity improvements.

So, does the key to better value for money lie in detailed service redesign, increased workforce flexibility and better people management? Yes, but management theorists have been arguing that for decades. The answer lies not so much in knowing what reforms are required, as it does in understanding how to motivate public sector managers.

The answer to this does not lie in education and exhortation. If that were the answer, then governments would have worked out the value for money equation decades ago. In some cases, the answer has been found in the heroism of an outstanding public service manager, who is willing to risk his or her career in personally underwriting a change agenda. But as Edmund Burke pointed out a long time ago, the foundations of good public management cannot be laid in rare and heroic virtues.

The Institute's analysis suggests that part of the answer lies at the competitive edge. Competition gives permission to public sector managers to innovate. It provides them with a mandate and an incentive to implement change. And it serves as a convenient conduit for the spread of new ideas across the public service sector as a whole